New paper - Paul Heggarty et al. ,Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages.Science381,eabg0818(2023).DOI:10.1126/science.abg0818

*Note, in the paper the authors use dates in BP (before present) where present = 2000 CE. While I appreciate the strictly secular nomenclature, I prefer BCE dates as they are easier to comprehend for my brain (for now). So I convert these into BCE by subtracting 2000. eg. 6000 BP = 4000 BCE. Do keep this in mind while reading. Thank you.

Brief Overview of the Method

This paper's Bayesian phylogenetic inference analysis is based on a new improved database (IE - CoR 1.0). The IE‑CoR 1.0 database contains data on relationships of cognacy (shared word origin) between 161 Indo-European languages in a reference set of 170 basic meanings. The new languages include the Nuristani branch, extinct Iranic languages from central Asia and a representative of sub-branches of Celtic which was missing from previous databases (Gaulish). The coverage prioritizes non-modern languages, providing a deeper phylogenetic signal and better chronological estimation. This database was contributed by 80 experts of different language sub-families to maximize data accuracy.

The authors state they improved the cognate encoding (keeping 1 lexeme for each cognate set rather than many synonyms used in previous databases which created lots of cognate sets per lexeme. This, for example, artificially elongated the branch length of modern Greek and the age of old Greek). The IE-CoR data set has highly consistent counts of cognate sets across all languages, very close to the target of 1 cognate set per meaning, per language. They also removed the constraints previously placed on ancient languages to be directly ancestral to modern languages which need not be the case. This previously forced 0 branch length (and therefore no divergence), simply forced the changes onto the next branch and elongated branch lengths artificially.

The database also solves the loanword problem in computational cladistics. "IE-CoR introduced the concept of loanword event, through which it has become possible to encode correctly both non-cognacy to the source lexeme, and subsequent cognacy between vertical descendants of that lexeme, once borrowed and fully integrated into the borrower language."

The IE-Cor database can be found here https://iecor.clld.org/

Important Discussion and Conclusions from the Paper

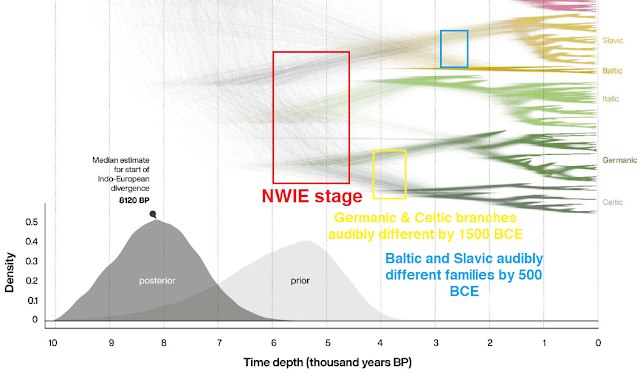

Heggarty et al reaffirm the position of the earliest Indo-European speakers in the south of the Caucasus around ~6100 BCE. They support a hybrid model in which the steppe was a secondary staging ground for European languages. Notably, the beginning of the split from Indo-Iranian into Indo-Aryan and Iranic is dated to ~3500 BCE, a finding wholly incompatible with the Andronovo hypothesis.

The authors make clear that Proto-Indo-European should include the stage before the Anatolian and Tocharian split, ie. they reject the nomenclature which places PIE in the steppe (which excludes at least the Anatolian branch) used, for e.g in Lazaridis et al 2022 (Southern Arc paper).

Similarly, recasting the question as if a search for the homeland of ‘Late Proto-Indo-European’ serves the same effect, by excluding the same two branches taken to have already diverged by the ‘Late’ stage, as if Anatolian and Tocharian were not relevant to the homeland question. There is in fact considerable inconsistency in linguistic nomenclature about different stages in the family’s diversification. Strictly, ‘proto-’ in any case refers by definition to the last stage of the common ancestor language of a family, immediately before any branches diverged. Proto-Indo-European should thus include Anatolian and Tocharian, since their relatedness with the other branches of Indo-European, in the same family, is not in doubt.

The authors argue for a non-steppe Asian route for Armenian, Greek and Albanian families based on their very early divergence dates. This is one of their conclusions that I am sceptical about, steppe ancestry does reach these regions at some point. However, I am not entirely sure about either theory.

Further south, the expansion of CHG/Iranian ancestry into the eastern Mediterranean and Balkans, without passing through the Steppe and thus without major admixture with EHG ancestry, presents a closer chronological and geographical match with the remaining, deeper European branches in our topology, namely Albanian, Greek and Armenian.

On the route taken by Iran Neolithic ancestry towards the steppe, they remain open to the east of the Caspian route but favour the direct route north from the Caucasus. Given my finding of Sarazm Eneo/Tutkaul neolithic-related ancestry in Steppe Eneolithic and Khvalynsk, I remain open to the east of the Caspian route.

On the route by which this CHG/Iranian ancestry reached the Steppe, aDNA evidence is not yet sufficient to exclude a route via Central Asia, i.e. first eastwards and then north and westwards, counter-clockwise around the Caspian, as hypothesized in (54). Nonetheless, the more parsimonious explanation, also given the aDNA record for time-transects through the Caucasus (48), would be a far shorter route directly northwards through the Caucasus, in line with corresponding expansions in material culture in the archaeological record.

On Indo-Iranian

The inference of an Indo-Iranic split at ~5520 yr B.P. (4540 to 6800 yr B.P.) may, at first glance, seem surprising. Established expectations are for a more recent date, based on the perceived level of similarity between Vedic Sanskrit and Avestan— the earliest known ancient languages in the Indic and Iranic branches, respectively. However, these judgments of linguistic similarity have been largely impressionistic (36) rather than quantified. In the precisely defined IE-CoR meanings, Early Vedic and Younger Avestan share only 58.7% cognacy (37). This matches the level of cognacy that survives between the most divergent sublineages within the Romance clade, for instance, after roughly two millennia since the spread of the Roman Empire. Early Vedic and Younger Avestan themselves date back to at least the mid-fourth and mid-third millennia before present, respectively. A time depth two millennia earlier (~5520 yr B.P.) for the split between their lineages (Indic versus Iranic) is thus consistent with the 58.7% cognacy overlap between them. More widely, ancient Indo-European languages show close similarities in some aspects of their inflectional morphology (noun declension and verb conjugation) and phonology. These similarities have often been assumed to imply a relatively short time span of divergence since their common ancestor language, but these impressions are also unquantified. Our time-depth estimate implies a long period of relative stability in these aspects, while early Indo-European diverged faster in other respects.

From Iran to India, Steppe ancestry is present only in low proportions, and only from a relatively late date, c. 3500 BP (49). This is significantly later than standard expositions of the Steppe hypothesis have proposed, associating Indo-Iranic with the earlier Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) culture. Dates for first incursions southwards from Central Asia as late as 3500 BP also leave little scope for the Indo-Iranic superstrate assumed to be present as far south and west as northern Syria and southeast Anatolia, already by the time of the Mitanni kingdom there.

Unlike the major and relatively sudden incursion of (Forest?) Steppe ancestry into Central Europe with Corded Ware c. 5000 BP, or Yamnaya into the Carpathian Basin around the same time, the weaker and much later signal in south-central Asia does not represent a strong prima facie explanation for the origins and first expansion of Indo-European languages here.

In the context of the Iran Neolithic ancestry, they write

It is found in eastern Iran, and in the Indus Valley (roughly the dividing line between the Iranic and Indic branches today), at the approximate time-depth when the two branches separate from each other in our analysis. This separation could correspond with an eastward expansion along the Ganges valley of what would become the Indic branch, picking up some of its distinctive linguistic characteristics from contact with local populations. This makes for a more straightforward scenario for the chronology, distribution and dominance of Indo-Iranic languages right across this region than a much later and genetically much less significant contribution from Central Asia.

For the steppe hypothesis for Indo-Iranian, they correctly point out the abysmal archaeological evidence (ie 0 steppe artefacts in India and Iran)

It has long remained a recognized weakness of the Steppe hypothesis (pp. 177-181 in (80); pp. 212-217 in (59); (90)) that the archaeological record lacks any obvious impacts out of the Steppe in a time-frame early enough to fit well with the scale of linguistic divergence within Indo-Iranic. Advocates of the Steppe hypothesis have widely assumed that the Andronovo culture ‘must have’ been Indo-Iranic-speaking, but even Mallory “find[s] it extraordinarily difficult to make a case for expansions from this northern region to northern India”, and more generally finds no obvious connection to “the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo- Aryans” (pp. 191-192 in (90)). The urban culture of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) was originally widely taken to offer the least bad candidate (7, 89, 90). Samples of aDNA from BMAC contexts, however, lack the expected Steppe ancestry, found only later.

To this, I add these golden words from CC Lamberg-Karlovsky (2004)

There is absolutely NO archaeological evidence for any variant of the Andronovo culture either reaching or influencing the cultures of Iran or northern India in the second millennium. Not a single artifact of identifiable Andronovo type has been recovered from the Iranian Plateau, northern India, or Pakistan.

In the main paper, they reject the steppe hypothesis for Indo-Iranian

In particular, in this hypothesis, Indo-Iranic, the major eastern branch of Indo-European,was one of the last two main branches to emerge, out of a final major clade with Balto-Slavic. Our results contradict this in both chronology and tree topology. Indo-Iranic branches off early, ~6980 yr B.P. (5650 to 8400 yr B.P.), and support for a common clade with Balto- Slavic is minimal, with a posterior probability of only 12.3%. Recent aDNA data from Central and South Asia have sought to trace movements of people into Western and South Asia by migrations southward from the steppe. However, for the period 4300–3700 yr B.P., samples from the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) do not yet attest to any such southward migration (49). Steppe ancestry is not found until ~3500 yr B.P., in the Gandhara Grave Culture in northern Pakistan, and only at limited proportions (49). The interpretation that this ancestry can be identified with the first Indo-Iranic dispersal into South Asia (49) is not straightforwardly compatible with our earlier date for the separation of Indo-Iranic from the rest of Indo-European (~6980 yr B.P.). We also find that Indic and Iranic had diverged from each other already by ~5520 yr B.P. (4540 to 6800 yr B.P.). To reconcile this with a steppe origin would require an alternative scenario in which Indic and Iranic split from each other approximately two millennia before entering South Asia and Western Asia.

They conclude a trans-Iranian-Plateau route for Indo-Iranian

Our hybrid hypothesis posits that out of this homeland south of the Caucasus, from ~8120 yr B.P., PIE began to diverge as early migrations split it into multiple early branches. One of these branches could have taken Indo-Iranic eastward far earlier than the Steppe hypothesis presumes, but in line with the linguistic chronology in Fig. 3, in which Indo-Iranic emerged as a distinct branch in the early phases of Indo-European divergence. Another main branch reached the steppe directly northward through the Caucasus ~7000 to 6500 yr B.P., compatible with one current interpretation of the aDNA record.

Here, I add that such migration has genetic evidence for SC Asia. In my previous post, I showed how the Tutkaul Neolithic ancestry from Tajikistan 6200 BCE was ~75% Siberian, but by 3600 BCE in Tajikistan, the Sarazm En individuals have a majority Iran Neolithic ancestry and only 20-25% Siberian-related ancestry indicating a gene flow from Iran between those two time periods. The spread of bread wheat from Iran to both India and SC Asia around 4000 BCE also alludes to some migration (Zhao et al 2023). The admixture date between Iran Neolithic and Andamanese-like ancestry in the Indus Periphery individuals was also around 4000 BCE (Narasimhan et al 2019) and the presence of significantly non-zero Anatolian ancestry in Indus Periphery individuals (Maier et al 2023) ensures that this ancestry entered post 6000 BCE via Iran, along with Iran Neolithic ancestry.

Accuracy of predictions

4. The split of the Proto-Romance language of the Italic family into Romanian, Sardinian, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish etc commenced between 200-500 CE which is in line with other estimates (Goldstein 2023) and is also consensus.

5. Balto-Slavic is shown to have formed a clade (Posterior Probability 0.63) with Italo-Celto-Germanic as part of a larger North-West-European language family. The split date of Balto-Slavic from the IE tree is said to be ~4500 BCE [95% CI range 3000-6000 BCE]. I definitely prefer the lower end of this range. A 4500 BCE date is too early.

The beginning of the Balto-Slavic split date into Baltic and Slavic is presented as ~1663 BCE (95% CI range of 531 - 3034 BCE). Given that Balto-Slavic modern populations require the specific B-S drifted sources (population bottleneck can cause large random drift) from Baltic_BA individuals (1200-500 BCE Estonia and Latvia) to model both groups, I feel that the lower end of that range is preferable. Although, the drift could have been in place much earlier than 1200 BCE since we don't have baltic samples from the prior period. This specific drift from Baltic_BA is not required to model other European IE groups like Germans, British, Irish etc.

6. According to the final tree, the breakup of proto-slavic begins around ~500 CE (95% CI range of ~200-800 CE) which is in line with mainstream consensus.

7. Anatolian and Tocharian are the first two to branch off, again following the consensus.

8. Armenian-Greek form a clade with a high posterior probability of 0.86, which is a mainstream view as well.

9. Within Indo-Iranian, Indic and Iranic branches begin separating by ~3500 BCE and are full separate by 3000-2500 BCE (based on DensiTree). This would correspond archaeologically to Indus Valley Civilization (Indo-Aryan) and Bactria-Margiana Complex (Iranic). IVC ancestry is present in all Indo-Aryan speakers from NW India to Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Similarly, BMAC-related ancestry is present in all Iranic speakers from ancient Scythians and Sarmatians to modern Tajiks, Yaghnobis, Afghans and plateau Iranians.

Indo-Aryan branching into Dardo-Nuristani and Middle Indo-Aryan seems to be complete by around 800-600 BCE (visually, based on DensiTree) which seems acceptable, although I haven't seen much research on this specific split.

Within the Iranic branch, West Iranic branching away from East Iranic seems to have been completed by ~900 BCE, just in time when Assyrians and Urartians noted Persians and Medes in West Iran. Tablets of King Shalmaneser III, dated to ~840 BCE note the kingdoms of Parsua and Medes to the east of Assyria, the earliest direct reference to Iranic-sounding kingdoms (https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/media)

This database included 7 ancient Iranic languages, and 2 ancient Indic languages, more than any used before (usually only Vedic and Avestan were includedbeforeo this paper) significantly increasing the power to accurately detect chronology within this grouping.

209 comments:

«Oldest ‹Older 201 – 209 of 209Also on a sidenote, CHG in Yamnaya is mostly male-mediated. See Lazaridis on twatter

https://nitter.net/iosif_lazaridis/status/1563953730499878926

So there's no contradiction between male-biased migrations and a potential language shift, especially if coinciding with new technology arriving on the steppe which transformed its lifestyle and even religion. (Which it did, see Khvalynsk paper)

Is this definite proof of anything? Probably not. Is it a very strong indication of what happened, given recent papers as well? Yes.

Is it also a very strong indication of what did NOT happen? Also yes. That's simply what the new data that comes out show

You know, people have to understand the level of expertise and knowledge in this field is actually very low, dismally low, even within within 'professional' spaces.

I actually just realised ALL the PCAs in this space are WRONG. The PCAs generated in this field are based in snps, they are actually PCAs of snps not of actual genetic distance.

The CORRECT was to run a PCA is to get meaningful genetic distance measures such as FST, F2 or outgroup f3 in a matrix form, and then run PCA on that data.

The current 'maintstream' way of running PCAs what it does is it produces is it looks at snp variation across the sample space, and aims to reduce this variation in terms of correlated snp. This can be useful when learning about the process of allele mutation and frequency change and different alleles are correlated and changing over time.

But it doesnt give you real population dynamics, it just gives you allele dynamics. So for instance it gets massively skewed by selection of important or useful alleles across populations, and it gives that process more weight than total drift.

These PCAs wont be consistent with other tools like qpGraph, fstats or anything else.

So you have to understand the level of 'science' is woefully inadequate and most of this needs re-evaluation.

These PCAs are meant to analyse the relationships between SNPs not Populations/individuals.

Did the taurine cattle domestication happened after Iran HG reached India?

@Rob mutts davidski come with a real username

"*Note, in the paper the authors use dates in BP (before present) where present = 2000 CE. While I appreciate the strictly secular nomenclature, I prefer BCE dates as they are easier to comprehend for my brain (for now). So I convert these into BCE by subtracting 2000. eg. 6000 BP = 4000 BCE. Do keep this in mind while reading. Thank you."

It is a minor point (I've commented elsewhere at length on the paper itself and don't need to do that again here several months later), but in archaeology, historical linguistics, and genetics, "BP" is defined as a matter of academic convention to mean years prior to 1950 CE, so that you don't need to consider the date of the publication to make BP dates in different papers comparable to each other.

Rob and Davidski are pathetic and wrong about everything.

Its pretty much a done deal by now, that there was a massive CHG expansion/invasion from the south (Iran or further south) and it was completely male mediated. indian/iran related males invaded the Steppe and killed many of the locals men and impregnated their women, giving rise to the corded ware and sintastha populations.

R1a is not native to the steppe, and neither is J1.

hello,

neither the Gray team nor this author have any knowledge of the definition of "Glottochronology". GC is just a subdisciplin of lexicostatistics by adding the aim of getting a time scale. It must not be confused with the different approaches to GC, as done here. Hans J.J.G. Holm

This tickles my brain

Post a Comment